This is a Guest Post by Alex @MacroOps which was posted originally here Another Lesson In Position Sizing From The Volpocalypse of 2018 and is reposted here with permission.

Most famous fund failures have leverage at their core. That’s the true culprit for disaster — not the actual trade ideas. Bad position sizing kills.

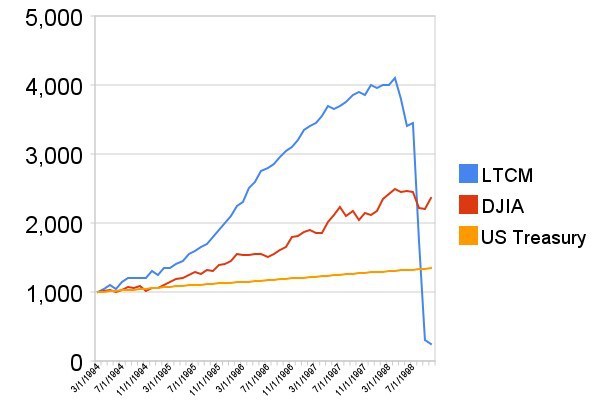

Long Term Capital Management’s strategy involved scanning the world for bond spreads that diverged from historical values — something known as convergence trading. When spreads diverged from their means, LTCM would buy the cheap and sell the expensive bond. Then wait for prices to revert back to their “theoretical efficient” market price and make a small profit.

But LTCM wasn’t satisfied with the tiny profits on the spread. They were “Masters of the Universe” and wanted to put up bigly numbers that smoked the S&P. So they took this simple strategy and leveraged up to high heaven.

Before LTCM was incinerated they had a portfolio market value of $129 billion. Of which, $125 billion was borrowed money. That’s a leverage ratio of 32:1.

Once old lady volatility hit the market, those bond spreads that LTCM had leveraged to infinity betting that they would quickly converge just like all previous times… kept diverging… and diverging. Until eventually LTCM was forced into liquidation.

Leverage and crowding caused the forced unwind of the trade. Not the strategy of buying cheap bonds and selling expensive bonds. LTCM had a good strategy that they ruined with excessive leverage.

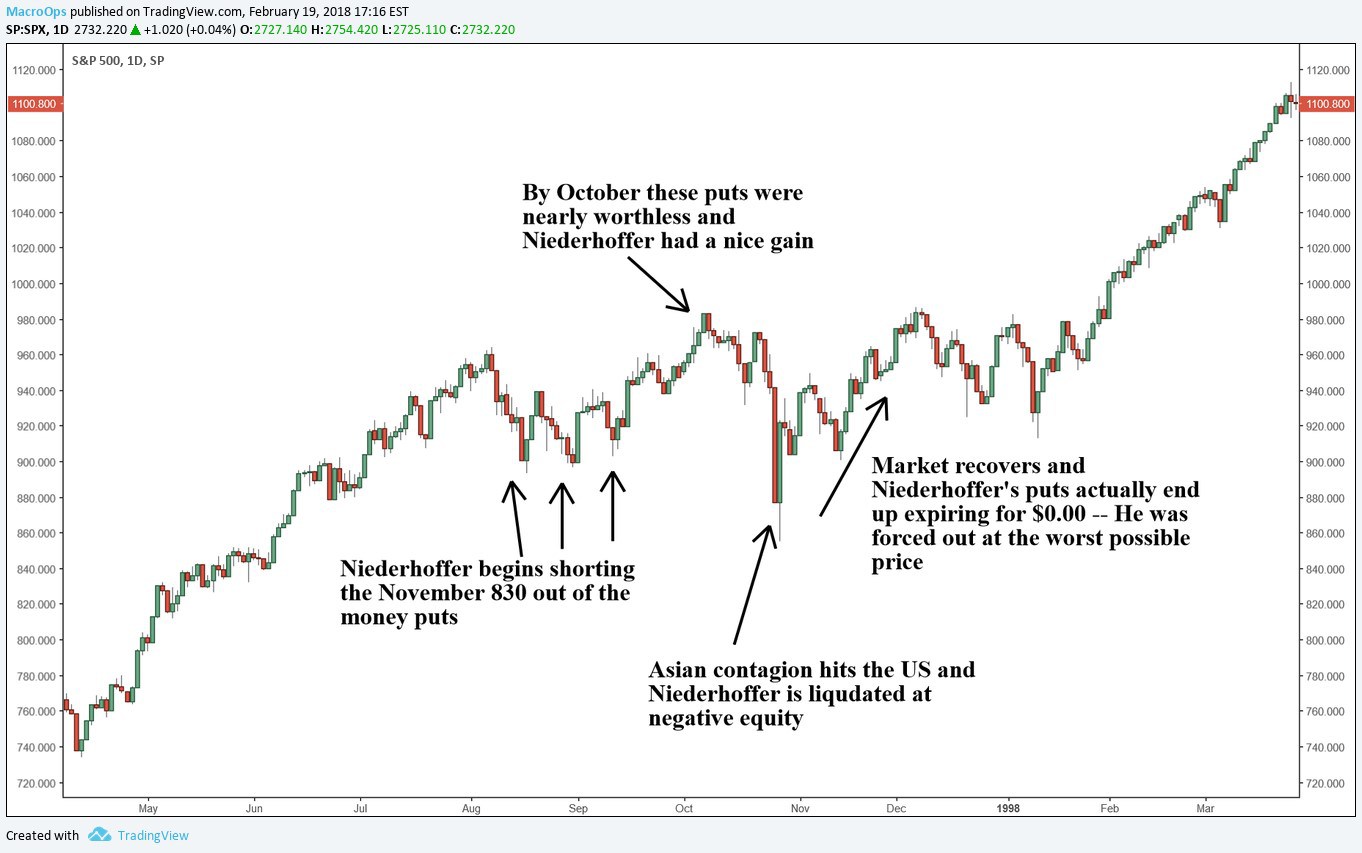

The exact same leverage issue happened to Victor Niederhoffer in 1997.

After suffering from a huge loss on Thai stocks during the Thai Baht crisis, Niederhoffer turned to aggressive S&P 500 put writing in order to “make back” his losses.

Over the summer of 1997 he shorted out-of-the-money November 830 puts for prices between $4 and $6.

By October these puts were trading for just $0.60 and Niederhoffer had a large gain. But the Asian Contagion spread and eventually hit the S&P.

On Thursday October 23rd, 1997 the puts rose to $1.20. On Friday the S&P dropped further but closed well above Niederhoffer’s option strike. Niederhoffer still wasn’t worried — his puts were trading for $2.40.

Over the weekend Asian markets continued to sell off. Hong Kong dropped 5% during its session which triggered a risk off move in the US markets driving stocks down 7%. This rout continued into the next morning sending the S&P spiraling into the 800s.

Volatility skyrocketed. And Niederhoffer’s puts shot up to $16. That’s 300% higher than the price he sold them for.

Refco, Niederhoffer’s broker at the time, was not happy. They called in his puts mid-morning on Tuesday October 28th for a loss of $90 million. Niederhoffer’s $70 million fund turned into a capital blackhole of -$20 million.

The market bottomed right after Niederhoffer was margin called. By November, the market was back near highs. His 830 puts went on to expire worthless — meaning his trade, had he been able to hold on, turned out to be profitable.

But his leverage forced his liquidation. He was oversized and couldn’t ride the trade out.

Niederhoffer had shorted so many puts that a run of the mill two-day market selloff sent him out on a stretcher.

If he had sized the trade correctly, he would have survived the ride and took home a small profit. But the guy was playing on tilt, got greedy, maybe a bit arrogant, and lost all of his client’s money. (Here’s an interesting clip of him post blow up)

With the trading history books filled with examples like these where hubris and stupid sizing led to catastrophe you’d think trader’s today would maybe, learn from the past. But of course that’s not the case. Human nature is after all, human nature. And “easy” money is quite effective at clouding our better judgement.

The Volpocalype of 2018 showed us that both amateur and professional traders are still making the same mistakes with position size and leverage.

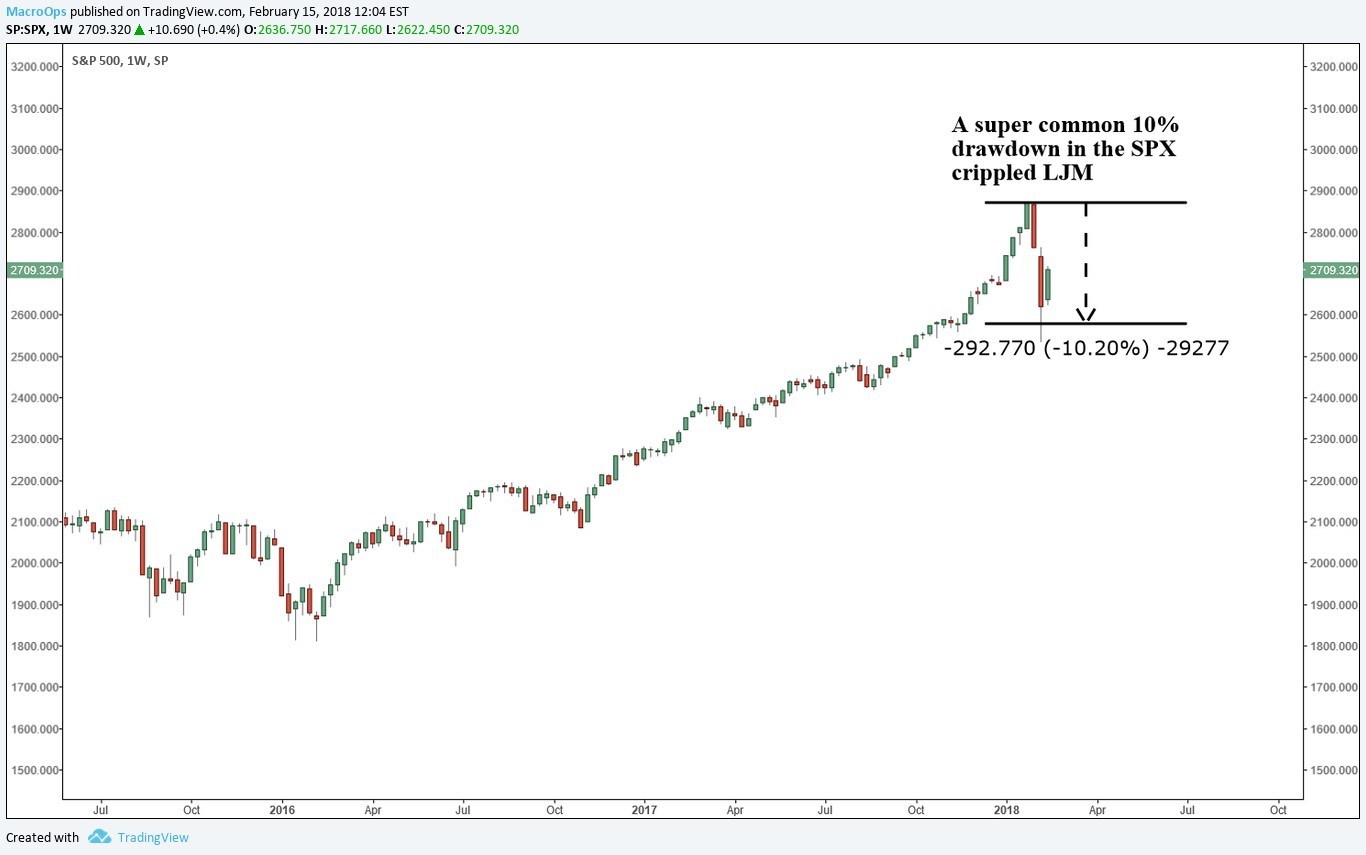

LJM partners, a mutual fund that sells options just like Niederhoffer did and whose tagline was “superior returns for the patient investor” followed the LTCM playbook.

A not-out-of-the-ordinary 10% fall in the S&P forced the fund to close positions at extremely unfavorable prices.

And then there was this amatuer XIV trader from Reddit who lost nearly $4 million dollars in XIV.

XIV goes up over time. But it also has incredibly nasty drawdowns that can exceed 90%. XIV trades more like an option than a stock. It has the ability to go up 100s of percent but also the ability to go down 90-100%.

Knowing this it’s crazy to think that anyone would allocate 100% of their portfolio into this exotic product.

So why did this Redditor do it?

Why did LTCM, and Niederhoffer and LJM carry such large positions?

Why do we constantly have a steady stream of stories about traders leveraging to the hilt and blowing out their accounts?

At the end of the day it all comes down to greed and hubris. It’s because traders want to turn a sound strategy that can produce 10% per annum returns into something that generates 30% per annum. And of course the only way to do this is to leverage the capital.

But as we’ve seen time and time again, the more you leverage the higher your chances are of ending the game bankrupt. And at a certain level of leverage your chances of going bankrupt actually converge to 100%.

That’s why it’s crucial to get position sizing right alongside a solid trading edge.

The late John Bender explains this perfectly in his interview inside Stock Market Wizards.

It might seem that if u have an edge, the way to maximize the edge is to trade as big as you can. But that’s not the case, because of risk. As a professional gambler or as a trader, you are constantly walking the line between maximizing edge & minimizing your risk of tapping out. ~ Market Wizard John Bender

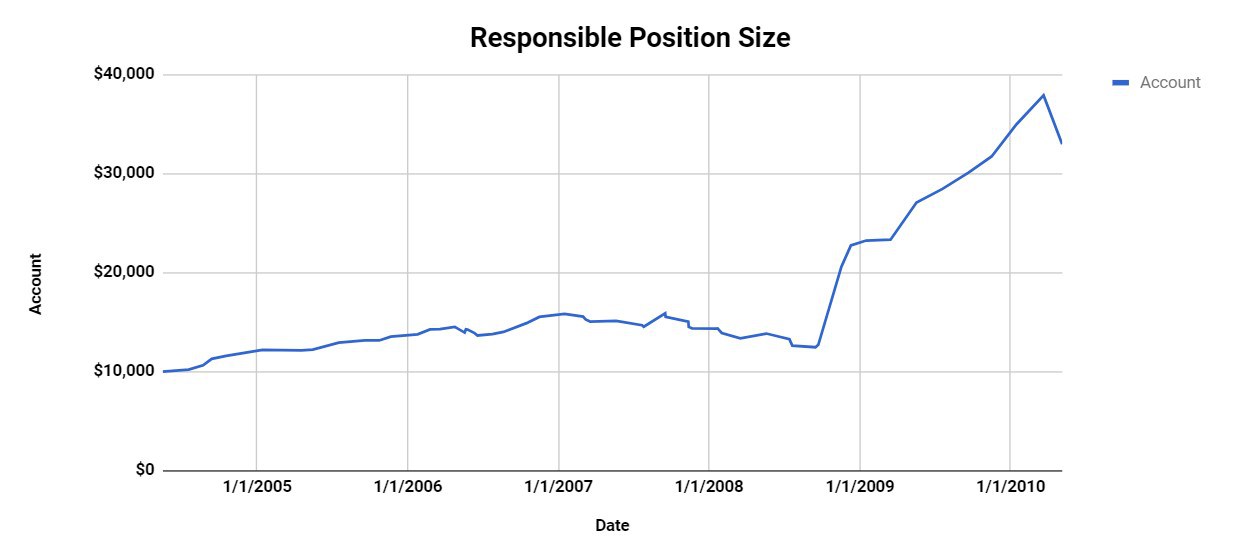

I can illustrate this concept with a simple example.

Here’s a decent “good enough” trading strategy that starts with $10,000 in account equity.

From mid-2004 to mid-2010 it did pretty well. $10,000 turned into around $33,000.

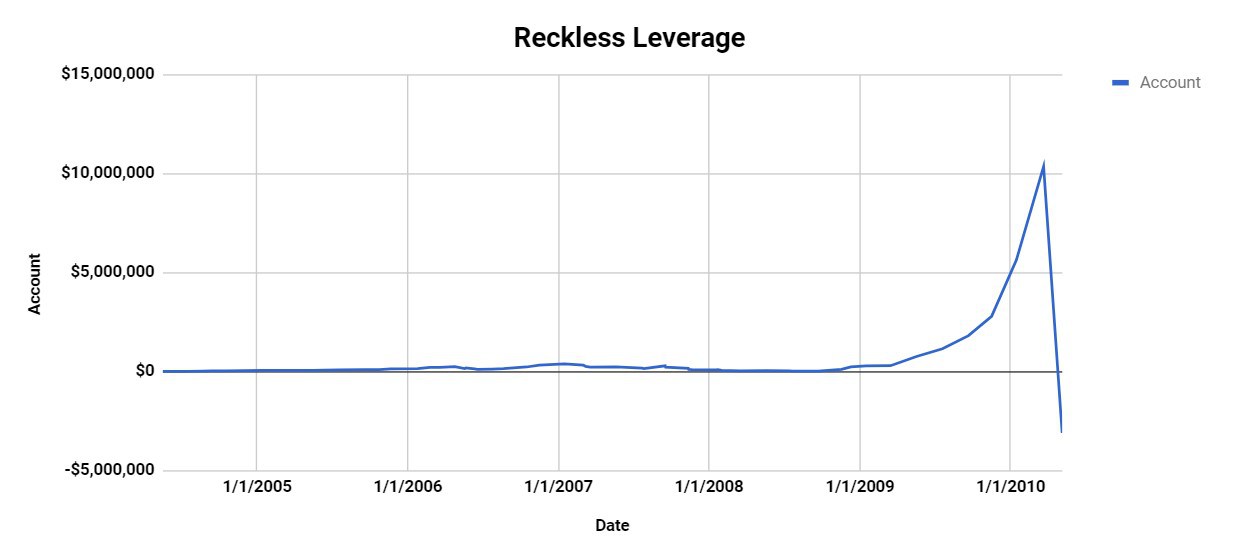

Now here’s the exact same trading strategy, with the exact same starting equity, but with 10x the position size.

The allure of leverage is obvious. The 10x model at its height had a 1000x gain. $10k turned into $10 million. The prospect of outsized returns is what lures traders to lever.

But it’s a farce. Using this amount of leverage guarantees a blow up will occur at some point. And unfortunately for this trader he didn’t stop and ended the game with a $3 million debt to the broker.

To position size correctly you need robust risk management assumptions. That means assuming any product can trade at any price at any time.

If your trading VIX for example, assume it can go from 10 to 100 overnight. That might sound asinine but in reality it keeps you safe. Because at the end of the day anything can happen.

By putting extreme scenarios in your universe you can devise a way to survive should it occur. This way of thinking will keep you from botching position size.

Traders that blow up and over lever don’t think like this. Instead they use models that rely on past data to estimate “probable” risk.

Throw those methods out. Historical data means nothing when it comes to risk management. The future will always bring something more intense than the past.

Another thing to be cognizant of is that strategies with negative skewness (frequent small wins and large rare losses) are especially tricky to position size correctly.

LTCM, Niederhoffer, LJM, and that XIV Redditor were all implementing strategies with negative skewness.

If you’re strategy has these characteristics it’s even more important to run extreme stress testing on your process and assume that your trading vehicles can trade at any price at any time. Size your positions from that extreme stress test. Never rely on past historical moves to define your risk in a negative skew trading strategy. The traders that rely on past data to size up risk always blow up.

Please think deeply about your position sizing process. If you don’t get it right you’ll end up in Taleb’s Turkey Graveyard with the rest of the traders who flew too close to the sun.

For more posts and information about Alex @MacroOps you can check out his website Macro-Ops.com.