This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. This post originally posted at “Who’s next in Trump’s trade crosshairs?” and is republished here with permission.

Since taking office, U.S. President Donald Trump has cast a shadow on many longstanding trade relationships. He’s pulled the U.S. out of what was going to be a transformative trade deal with Asia. He’s attacked Japan’s and Korea’s trade policies. Threatening a trade war with China was a staple of his campaign for the presidency. He’s talked about imposing a tariff on goods imported from Mexico.

With a new victim almost every week since his inauguration, what country could be next in Asia on his hit list?

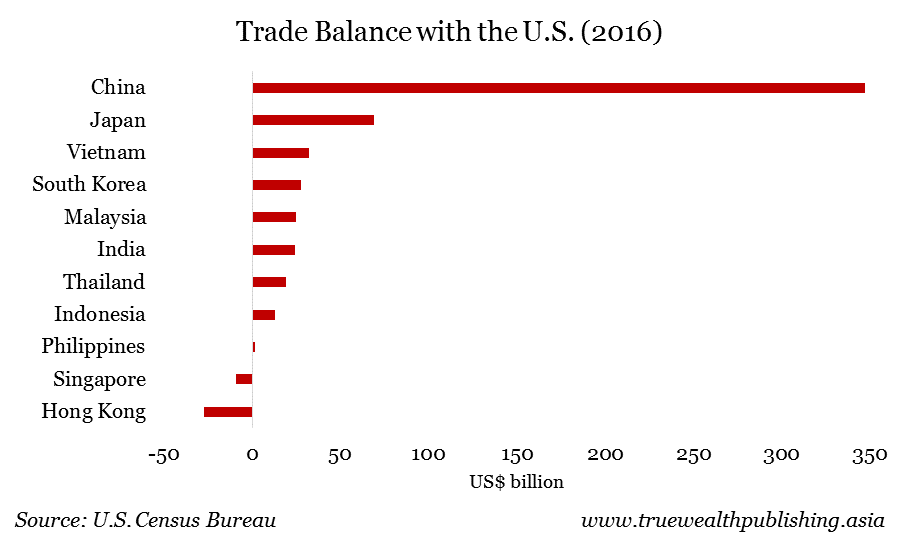

Countries posting a trade surplus with the U.S.

One way to predict Washington’s next move is to look at countries that run a large trade deficit with the U.S. A trade deficit is the amount by which the cost of a country’s imports exceeds the value of its exports. If the U.S. runs a trade deficit with country X, it means that a country X sells more to the U.S. than the U.S. exports to country X. There’s nothing inherently wrong with running a trade deficit. But a trade deficit is like a red flag to a bull for a U.S. government focused on bringing manufacturing jobs back to U.S. soil.

As the graph below shows, China is the leading offender. The country posted a US$347 billion trade surplus in 2016. (If a country runs a trade surplus with a trading partner, by definition the partner is running a trade deficit.) After China, in 2016, Japan, Vietnam and South Korea are the next three Asian countries that have the biggest trade surpluses with U.S.

In contrast, the U.S. actually runs a trade surplus with Hong Kong and Singapore. (Still, in November, Trump singled out Singapore as a country that’s taking jobs away from Americans.)

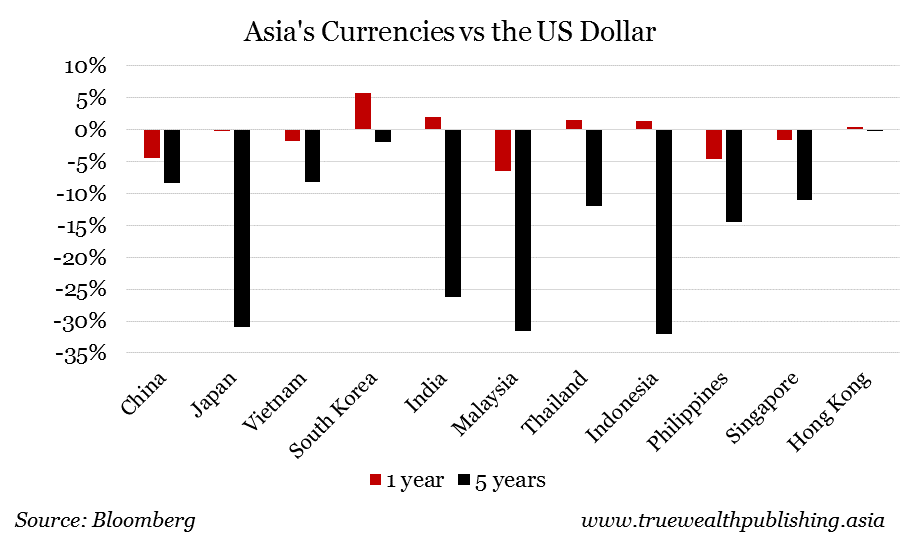

Currency “manipulators”

Another issue raised by Trump administration is whether a country is “artificially” trying to achieve an “unfair” trade advantage with the U.S. by causing its currency to fall in value. A weaker currency relative to the U.S. dollar makes that country’s imports cheaper in U.S. dollar terms. And a weak currency is an important factor in the trade balance.

By this measure, Japan, Indonesia, India and Malaysia are the biggest culprits over a five-year time horizon, as shown below. These countries have seen the greatest weakening (that is, depreciation) in their currencies relative to the U.S. dollar. Over the past year, the Philippines, China and Malaysia have seen the most depreciation.

One of the U.S. government’s contentions has been that China has been trying to manipulate its currency to gain an unfair trade advantage over the U.S. But in fact, China has been trying to prevent the depreciation of its currency – not promote its depreciation.

According to a U.S. Department of the Treasury report, “China’s intervention in foreign exchange markets has sought to prevent a rapid RMB [or renminbi, China’s currency] depreciation that would have negative consequences for the Chinese and global economies.” The department estimated that from August 2015 through August 2016, China sold more than US$570 billion in foreign currency in an effort to prevent rapid depreciation of its currency.

The U.S. government is constrained in what it can do to retaliate against offending trade partners by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. And as the U.S. steps away from its prior role as the custodian of global trade, China is ready to fill the gap with a raft of other trade deals.

This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight in Asia and around the world. You can also follow them on Twitter @stchresearch .