This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. This post originally posted here at Why investors should be happy – when consumers are not. It is republished here with permission.

When consumers are feeling upbeat – about their income, jobs, and life – it should be good for the stock market. Or should it?

Credit card company MasterCard regularly conducts a consumer confidence survey throughout 17 Asia-Pacific region countries, in which it polls consumers about their feelings on five economic factors including the economy, employment and income, the stock market and their quality of life.

In the latest survey, consumer confidence in both Singapore and Hong Kong scored in the low-30s – with 100 being extremely optimistic, and zero being darkly suicidal. The most optimistic countries – markets where people are buying stuff, hiring people, and doing other things that will boost the economy – were Myanmar (with a hard-to-believe score of 99.8) and India (97.6).

The last time consumer confidence in Singapore and Hong Kong was so low was in June 2009, near the end of the global financial crisis. Confidence levels have fallen more than 10 points since the end of 2015.

In the same way that strong economic growth is not necessarily good for the stock market, though, happy consumers are also not good for the stock market. And (similar to economic growth), lower consumer confidence is often a signal that stocks are about to head higher. Consumer confidence and stock markets tend to bottom out at about the same time.

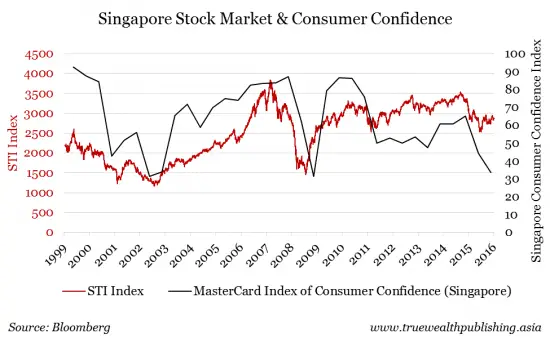

The following chart shows the performance of Singapore’s Straits Times Index (STI) compared to Singapore’s consumer confidence index.

Since the turn of the century, a fall in consumer confidence has preceded a recovery in the STI a number of times. The consumer confidence index previously hit lows in December 2002, June 2009, December 2011 and December 2013. And on every occasion, the market started to rally (to varying degrees) just before, or at about the same time, that consumers were feeling the least optimistic.

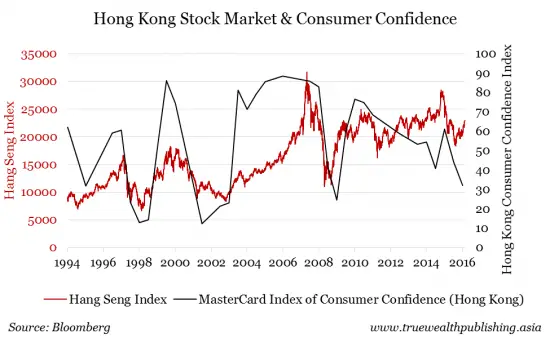

Hong Kong shows a similar trend. Pessimism in Hong Kong has in recent years preceded a rally in the Hang Seng.

Why is this? In general, factors like consumer confidence and economic conditions are “priced in” to the stock market. So by the time consumers are upbeat and optimistic, stocks have already moved up, and are poised to fall (this doesn’t bode well for India’s stock market). On the other hand, low consumer confidence suggests that shares are in a good position to rise.

Remember, share prices don’t reflect what’s happening right now. They reflect what investors think is going to happen. So it’s possible to make money in stocks during normal times. But the biggest gains come after the economy has been doing poorly.

Over the long term, consumer confidence is important for share prices. But in order for confidence to rise, it has to be low.

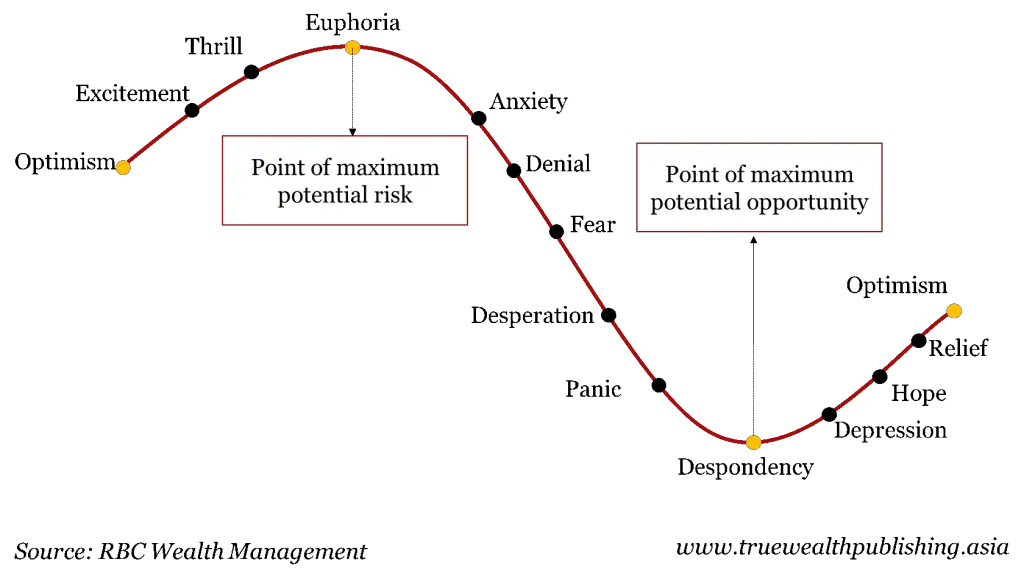

The following chart illustrates this cycle of emotions. It shows how growing optimism often means markets are at more risk of a fall. But the point of maximum pessimism often presents the best buying opportunities.

Cycle of Investor Emotions

If the latest consumer confidence results are indeed a sign of “despondency,” it also suggests that Singapore and Hong Kong investors are facing the point of “maximum potential opportunity.”

Markets can always go lower and consumers can get more pessimistic. But using history as a guide, investors in Singapore and Hong Kong should be feeling very optimistic about the prospects of the local stock market.

Kim Iskyan

This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. You can also follow them on Twitter @stchresearch .