This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. This post originally posted at Why your portfolio should look like a Premier League team and is republished here with permission.

Imagine you’re the head honcho of a professional sports team that’s going to be part of a new global super-league… football or basketball or baseball or (insert your favorite international sport here). You have a big budget to buy players, and you can select them from anywhere in the world. Your job is to create a championship-caliber, high-performing team that will win big.

So… if the team you’re building is the New York Knockers, would you focus mostly on American players? Or… if you’re in Singapore, would you hire mostly Singaporeans to play for the Singapore Slaughterers? And if you’re staffing up the Australian Koala Bears, would you favour home-grown players?

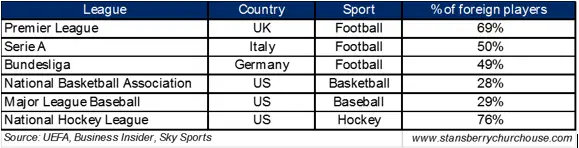

If you’re in it to win (and you are)… of course not! The world’s most successful sports leagues draw talent from everywhere in the world. That’s how they win. If Italy’s top-level Serie A soccer league only had Italian players, a consortium of Chinese investors would not be buying AC Milan for US$785 million.

What does this have to do with your portfolio? More than you might think.

Most people stock their portfolio with local players

A lot of investors – the vast majority of investors in big countries, in fact – fill their team (portfolio) disproportionately with local players (stocks and other assets). This is called home country bias. It’s when investors tend to have excessive exposure to their local market.

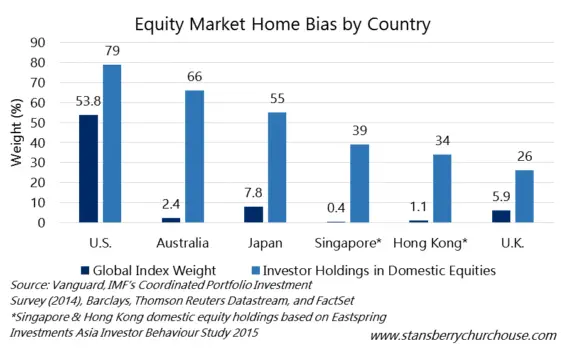

As the graph below shows, American stocks account for only 53.8 percent of total global market capitalization (that is, the value of all stock markets in the world). But the average American with a stock portfolio has 79 percent of her money in U.S.-listed stocks. Similarly, Japan accounts for only 7.8 percent of the world’s stock market capitalization. But investors in Japan put about 55 percent of their money in Japan-listed stocks. And people in Australia have two-thirds of their portfolio in local shares – although Australia accounts for just over two percent of the world’s markets.

And Singapore’s stock market is only 0.4 percent of the world total, but Singaporeans invest about 39 percent in domestic equities.

If you focus only on local players, you might win, for a while, but…

It won’t last forever. Maybe you recruit mostly (say) Chinese football players for the Shanghai Shooters franchise of the new global super-league… and you happen to stumble into a once-in-a-generation crop of immensely gifted local talent. And you win. That is: You win – for a while.

Something similar can happen with markets. Over the past several years, if you’re in the U.S. and you’ve been stocking your portfolio with American players – shares, that is – you’ve done really well. The S&P 500 has been a sterling outperformer, as shown below.

But sooner or later – and mean reversion suggests sooner – U.S. markets will stop outperforming. And as we’ve written before, U.S. markets are primed for a correction.

At that point, you’ll want to have more international players on your team… that is, foreign stocks in your portfolio. Other markets will outperform, and being heavy with home players will penalize you. You don’t want to diversify by market capitalization. But just because a stock doesn’t speak your language doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have it in your portfolio.

Why do investors succumb to home country bias? Mostly because it’s easier and more comfortable. We’ve also said that you should invest in what you know. But you should expand what you know. That’s what our flagship publication The Churchouse Letter is all about: expanding your investment horizons and expertise and helping you become a better-informed investor.

From a portfolio diversification perspective, investing mostly – or only – in your home market is a recipe for disaster.

Good investing,

Publisher, Stansberry Churchouse Research