This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. This post originally posted at How to turn dumb money into smart money and is republished here with permission.

After a series of poorly timed investments, have you ever turned to a friend and said jokingly, “If you want to make money in the markets, just do the exact opposite of what I do?” If that sounds familiar, you may have been a victim of the “Dumb Money Effect.”

The Dumb Money Effect has nothing to do with how smart you are. It refers to the tendency of money to flow into funds or stocks when prices are rising and out of investments when prices are falling. Both big institutional and smaller individual investors have been guilty of it.

However, studies of various markets around the world show that the average investment fund investor in particular has an uncanny ability to pick the worst funds at the worst possible times.

For instance, the U.S. S&P 500 index, including dividends, has averaged about 9.5 percent annual returns over the past 20 years. The returns for actively managed mutual funds were 1 to 1.5 percent less. That isn’t surprising, given the funds’ expenses and fees.

However, the average investor in the same funds earned another 1 to 2 percent less than the average investment fund.

Individual investors did not just “buy and hold.” Instead, they had a strong tendency to buy more shares of the funds as their holdings became more valuable, and sell shares of the fund as prices fell. The net result was that individual investors as a group underperformed the buy-and-hold mutual funds by about 20 to 40 percent.

The Dumb Money Effect, in which investors get scared and sell into down markets and then get optimistic at market tops, is so prevalent that there are “Dumb Money Indicators” for many markets. These are used by “contrarian” investors to profit from doing the opposite of dumb money.

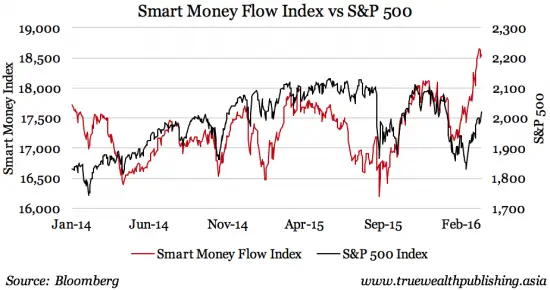

The chart below shows the Smart Money Flow index. It measures how much large, institutional traders bet against what the majority of average investors are doing on any given day. It basically shows that most average investors sell more when markets are at or near their lowest levels. Buying when individual-investor selling became extreme would have been profitable.

How can investors as a group be so consistently wrong?

We’ve discussed a number of behavioral “biases” that tend to lead to impulsive, emotional decisions by investors. These involuntary behaviors evolved from a time when split-second decisions often meant the difference between life and death.

At the root of the dumb-money effect is “outcome bias.” People tend to judge how good a decision was based on how things turned out. When we look back and judge whether a decision was good or bad, we tend to give too much weight to the outcome. If things turned out well, we believe it was a good decision. A poor outcome meant a bad decision.

To illustrate outcome bias at work, let’s use an example from the world of football. Your favorite team is preparing for the championship game. The team has one of the best goalies in the league, but two days before the big match, he twists his ankle in practice. After watching the goalie favor his other ankle before the game, the coach decides to play the backup goalie instead of the injured starter. Your team loses the championship game, 2-1.

After the game, fans are angry, calling for the coach to be fired. “What was he thinking? The No. 1 goalie was better on one leg than the inept backup!”

The fans’ post-match negative assessment of the coach’s pre-match decision was heavily influenced by outcome bias. Certainly, with a break or two, their team would have won and the coach’s decision to switch goalies would have been a non-issue, or even praised. But, in the fans’ eyes, the loss made it a bad move on the coach’s part.

Of course, that’s an unfair conclusion. Unlike his post-match critics, the coach made the decision to bench his star goalie without knowing what the outcome would be. The coach saw that the goalie was less than 100 percent before the match and made the best decision he could, given the information he had. Any judgment of the coach’s decision must be based only on the factors present before the outcome was known.

Similarly, investors have a strong tendency to decide which investments are good or bad based on recent price performance. They think that if everybody is buying something, it’s a good investment, and if everyone is selling, it’s a bad investment.

As we discussed previously, however, market prices are highly prone to mean reversion – the tendency of asset prices to eventually go back to the average. Dumb money is consistently on the wrong side of mean reversion. Smart money anticipates mean reversion and exploits it for profit. Successful investors invariably go against the dumb-money crowd – they buy low and sell high.

How can you avoid being part of the dumb money crowd?

- Study the history of the stock, fund or market you plan to invest in. Note how rising prices always pull back and falling prices eventually rally. Profit from mean reversion. Be patient.

- Study the investment’s present situation. What does it say about future returns? Base your decision on the merits of the investment, not on recent price action.

- Make an informed prediction about the stock or market based on price history and valuation. Create a rational plan and follow it.

As an investor, it’s not easy to go against the hard-wired instincts that compel us to make impulsive, unprofitable decisions. But, by carefully researching and planning your investment decisions, you can avoid the dumb-money crowd and join the profitable ranks of smart money.

This is a guest post from Kim Iskyan, publisher of Stansberry Churchouse Research, an independent investment research company based in Singapore and Hong Kong that delivers investment insight on Asia and around the world. You can also follow them on Twitter @stchresearch .