This is a Guest Post by Alex @MacroOps which was posted originally at: Current Target: Populism & Europe’s False Trend This post is republished here with permission.

One of my favorite sci-fi series is The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov. The book was first published in 1951 and is a grand “space opera” that takes place in the distant future. At the heart of the series (and what makes it so interesting) is the fictional philosophy of “psychohistory”.

Psychohistory is a blend between mass-crowd psychology and probability theory. It’s founded on the principle that while it’s impossible to predict actions at the singular individual level, you can still successfully apply statistical probability theory at the group level to predict the general flow of future events.

Asimov discusses how he came up with the idea of psychohistory in the following interview:

At the time I started these stories, I was taking physical chemistry at school, and I knew that because the individual molecules of a gas move quite erratically and randomly, nobody can predict the direction of motion of a single molecule at any particular time. The randomness of their motion works out to the point where you can predict the total behavior of the gas very accurately, using the gas laws. I knew that if you decrease the volume, the pressure goes up; if you raise the temperature, the pressure goes up, and the volume expands. We know these things even though we don’t know how individual molecules behave.

It seemed to me that if we did have a galactic empire, there would be so many human beings—quintillions of them—that perhaps you might be able to predict very accurately how societies would behave, even though you couldn’t predict how individuals composing those societies would behave.

So, against the background of the Roman Empire written large, I invented the science of psychohistory. Throughout the entire trilogy, then, there are the opposing forces of individual desire and that dead hand of social inevitability.

Like Asimov, we view people at the individual level similar to gas molecules; unpredictable and seemingly random.

But if we pull back and view large groups of people such as societies and nations, we find that their collective decisions under certain conditions are not only explainable, but completely foreseeable.

In a sense, the broad strokes of history are predictable while the details are not.

And just as we need to understand the “gas laws” to predict the behavior of gas on a macro level, so too do we need to understand the “laws of social history” if we want to anticipate the grand tide of human affairs.

There are three socio-economic truths that we know of:

- Nations (large tribes of people) are relatively open and peaceful when their standard of living is perceived as improving.

- Nations become closed and retaliatory when their standard of living is perceived as getting worse.

- We measure our standard of living on a relative scale. It’s better for a society to benefit less, if all together, than for parts of the society to materially benefit more than others, even if the standard of living is higher for all. When there’s a large gap between those who benefit and those who don’t, the society becomes increasingly susceptible to its “baser” tendencies.

Take these laws and combine them with our knowledge of debt cycles and you get a powerful framework to help understand history and present day geopolitics.

The long-term debt cycle (75-100 years) is where debt accumulation over a generation drives consumption and quickly raises living standards. At its zenith, a large chasm forms between debtors (those saddled with a mountain of debt) and their prosperous creditors (those with all the capital).

This long-term debt cycle inevitably leads to a society of Haves and Have-nots. As stated in our laws of social history, this relative prosperity gap leads to a closed and vengeful society.

Through this lens it’s clear that the rise of populist leaders across the Western world in the 1930’s was not some historical anomaly, but something completely expected, as was the world war that followed. When people feel their standard of living getting worse, they become angry. They elect someone to “fix” it regardless of the means. This is par for the course during the turning of the secular debt cycle (which last occurred in the 30’s).

Now, nearly 90 years later, we once again find ourselves in another secular deleveraging. And we’re currently in the early stages of attempting to rectify the gap between the Haves and Have-nots.

This relationship between the long-term debt cycle and populist policies can be seen in the two charts below.

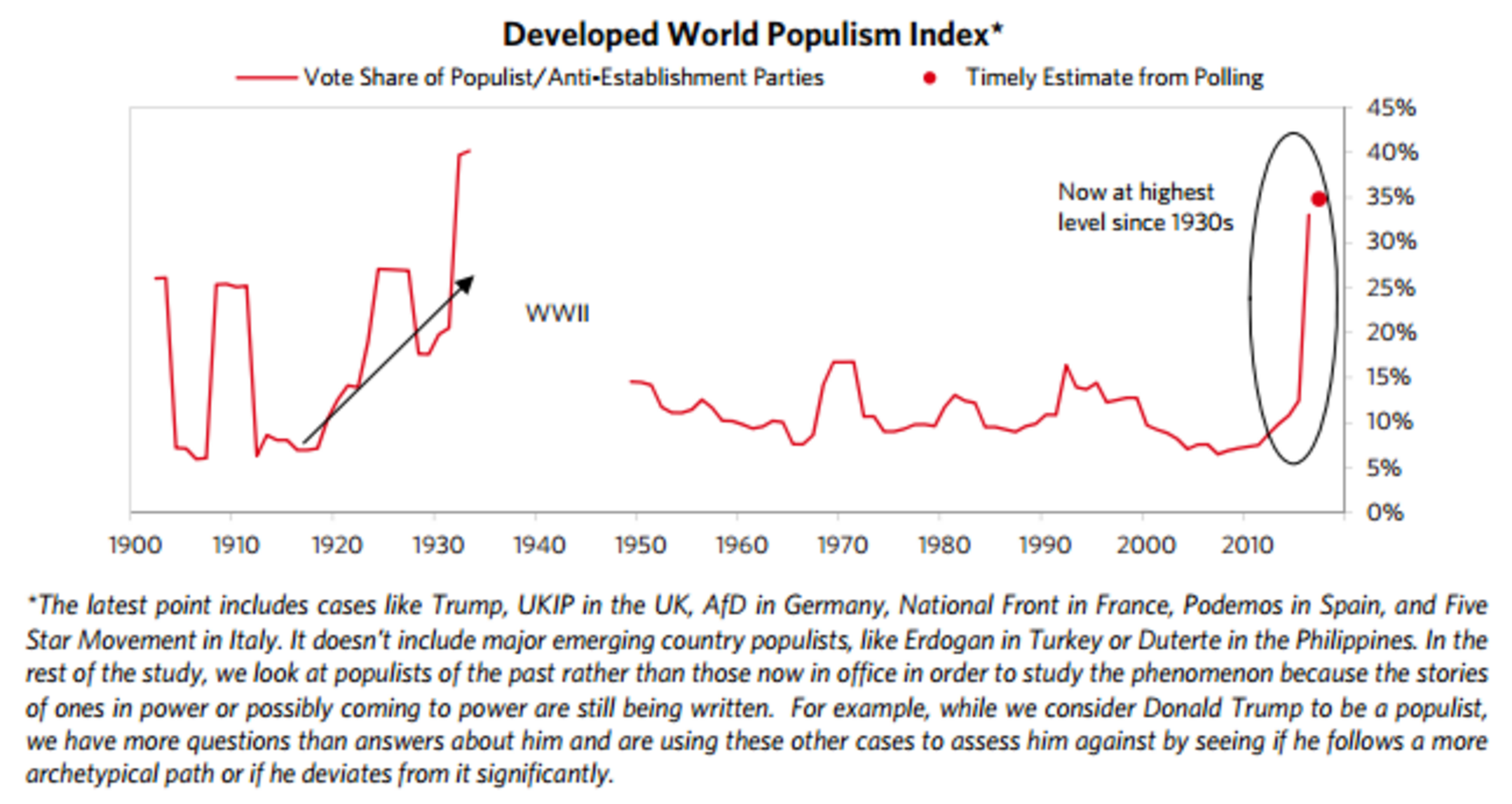

The first is from Bridgewater — the most successful hedge fund of all time. It shows their index that tracks populist votes throughout the developed world.

The chart has gone vertical since the Great Financial Crisis. The last time we saw these levels was during the Great Depression and the destructive two decades that followed.

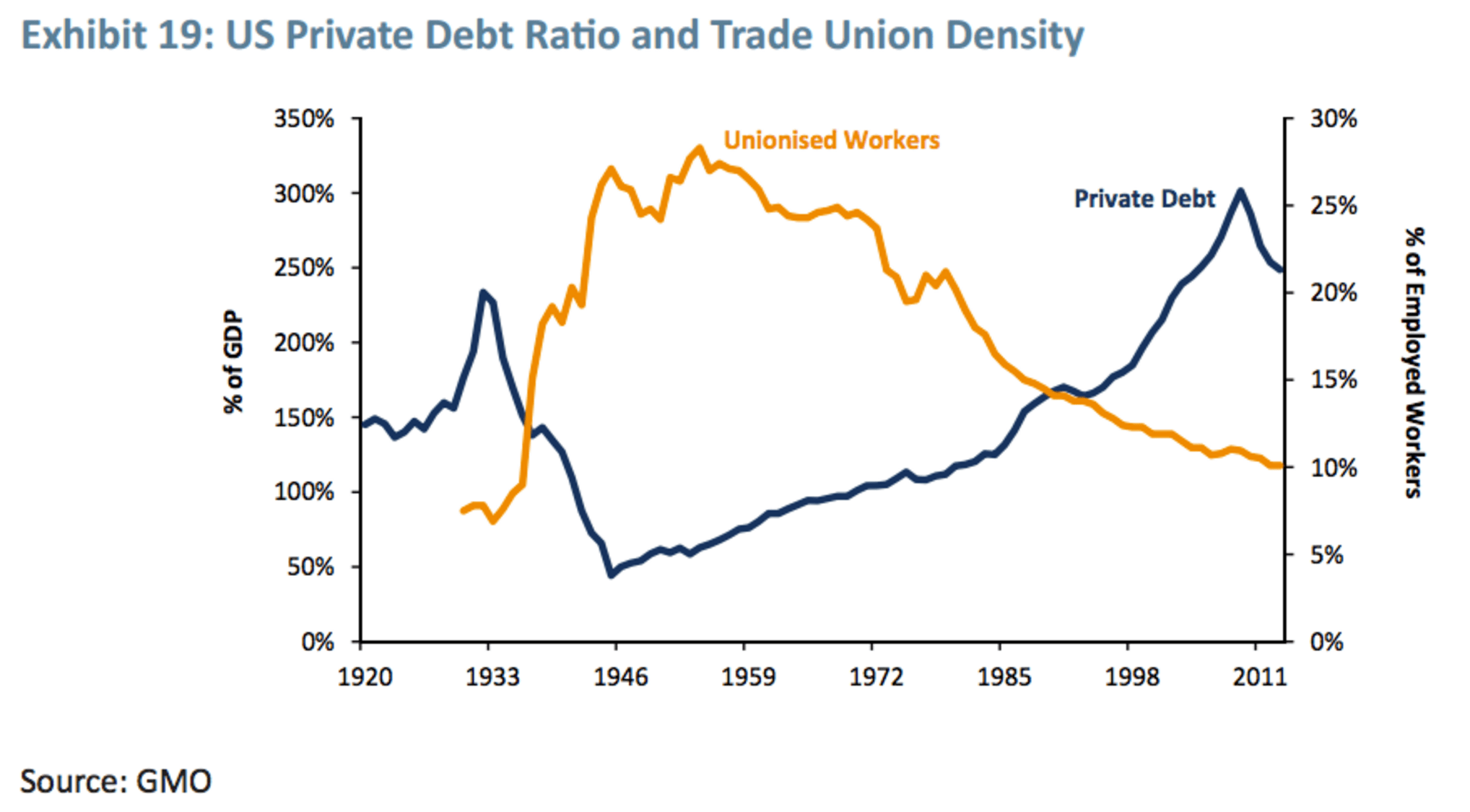

Now compare that chart to the following from GMO. It shows that private debt levels peaked at the height of the Great Depression alongside the percentage of unionised workers in the workforce.

There’s a virtuous cycle at work here.

The start of the long-term debt cycle sees rising living standards that create acceptance and complacency across a society. This complacency allows power to concentrate among those who have capital, while shifting it away from those who don’t (ie, labor).

This goes on until a saturation point is reached. Eventually, increased debt can no longer add to productive means. At this point laborers’ living standards start to stagnate or fall, creating an increasing level of wealth disparity. This is when the debt cycle kicks into reverse.

Labor unifies and the Have-nots battle the Haves for more power. At the same time, a debt deleveraging occurs and then the whole cycle starts anew.

With our “psychohistorical” framework, it’s safe to assume that populism, as a political movement, is in its early stages of a secular uptrend. Over the next decade or two there will be less global cooperation, more protectionism, and greater proclivity for global conflict. And it’s through this framework that we can get a clear view of what’s currently going on in Europe…

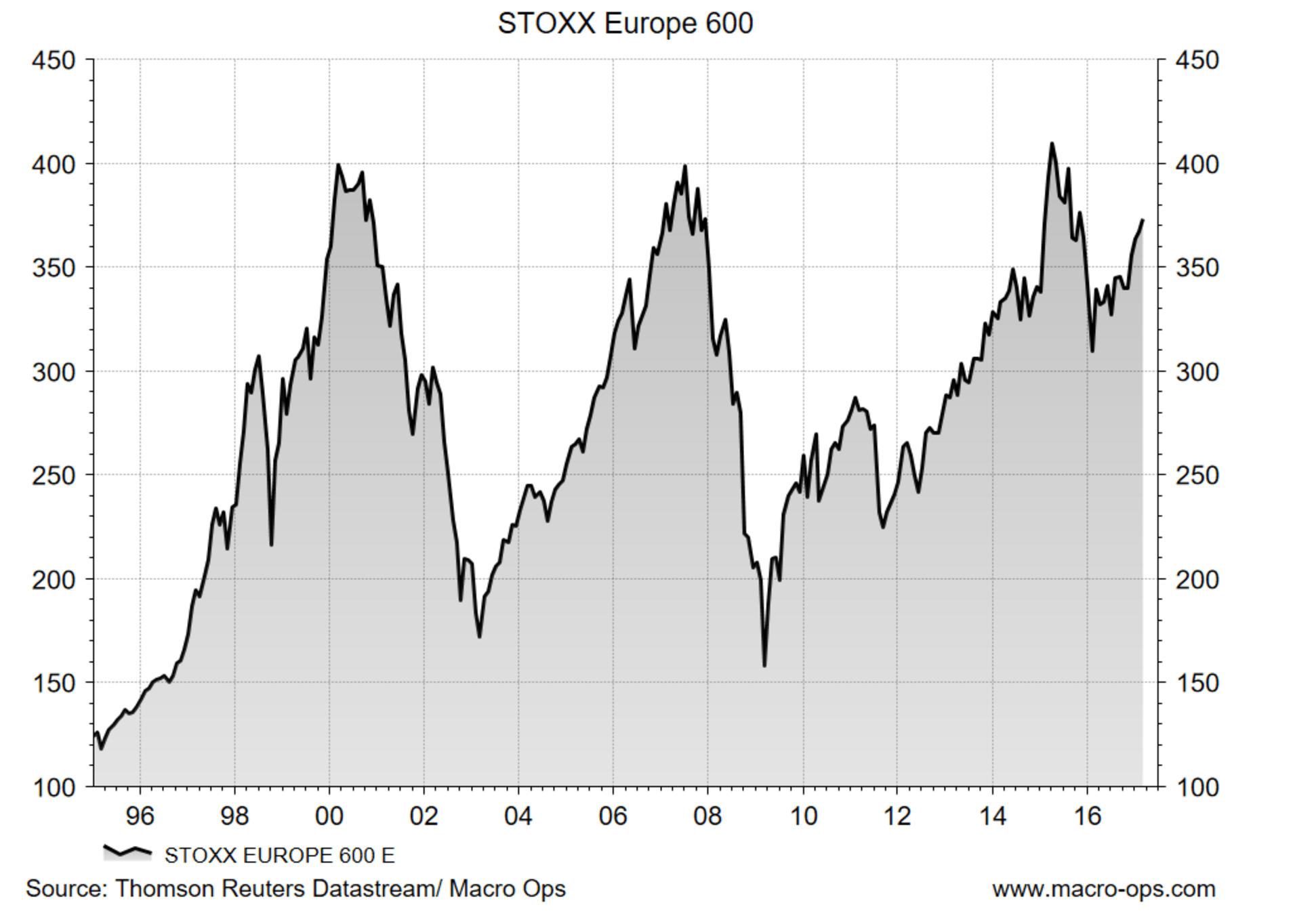

Charts of a number of European ETFs and indices look constructive.

The bullish narrative here is simple.

Relative to the US, European stocks are cheap. The US stock market is trading at a CAPE of 29x (the second highest reading in history) while Europe is trading at 18x. This isn’t cheap, but it’s a bargain compared to the US.

There’s also the case of diverging monetary policy.

The Fed is tightening rates with two more hikes planned this year. There’s serious talk of reducing the balance sheet following the third hike as well.

This is in stark contrast with Europe, where the deposit rate is -0.4% and the ECB is still conducting large scale quantitative easing. They’re buying €60B worth of bonds every month…

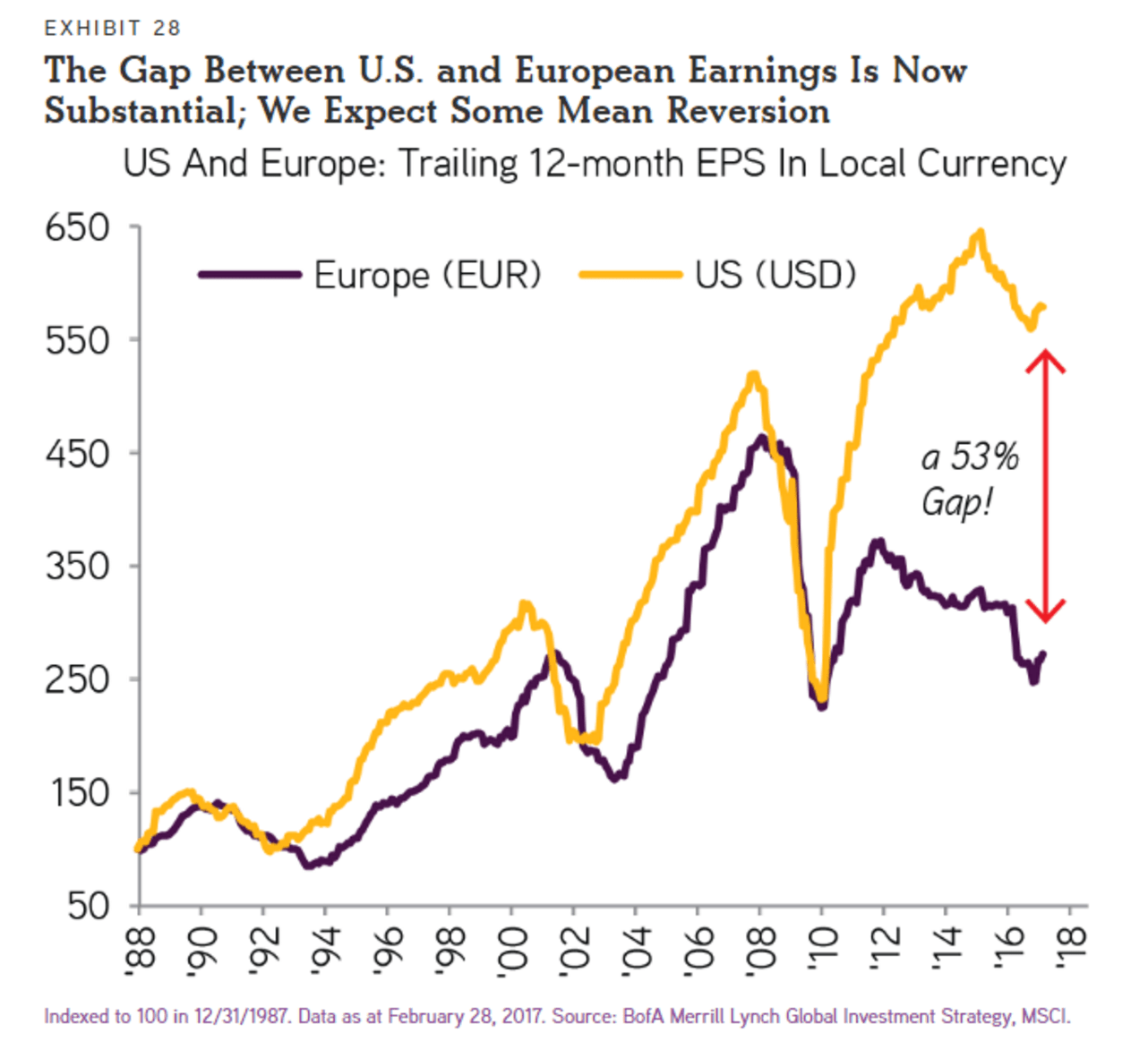

There’s also the assumption that the large EPS gap between US and European stocks will mean revert, with Europe doing most of the work to move its EPS higher.

These factors form the basis of the European bull case. Relative valuations, diverging monetary policy, and mean reversion in EPS set the stage for a run in European stocks.

This is why fund managers have been jumping into the trade since the end of last year.

A catalyst that would ignite this positive trend further would be the defeat (or the perception of the inevitable defeat) of presidential candidate Marine Le Pen in the upcoming French elections.

Le Pen is the populist leader of the right wing National Front. The National Front is an anti-euro, anti-immigration party. A Le Pen win would send shockwaves across Europe… signaling the demise of the EU as we know it.

She’s currently not projected to win. But we all know how well the polls have performed in the last two major political events…

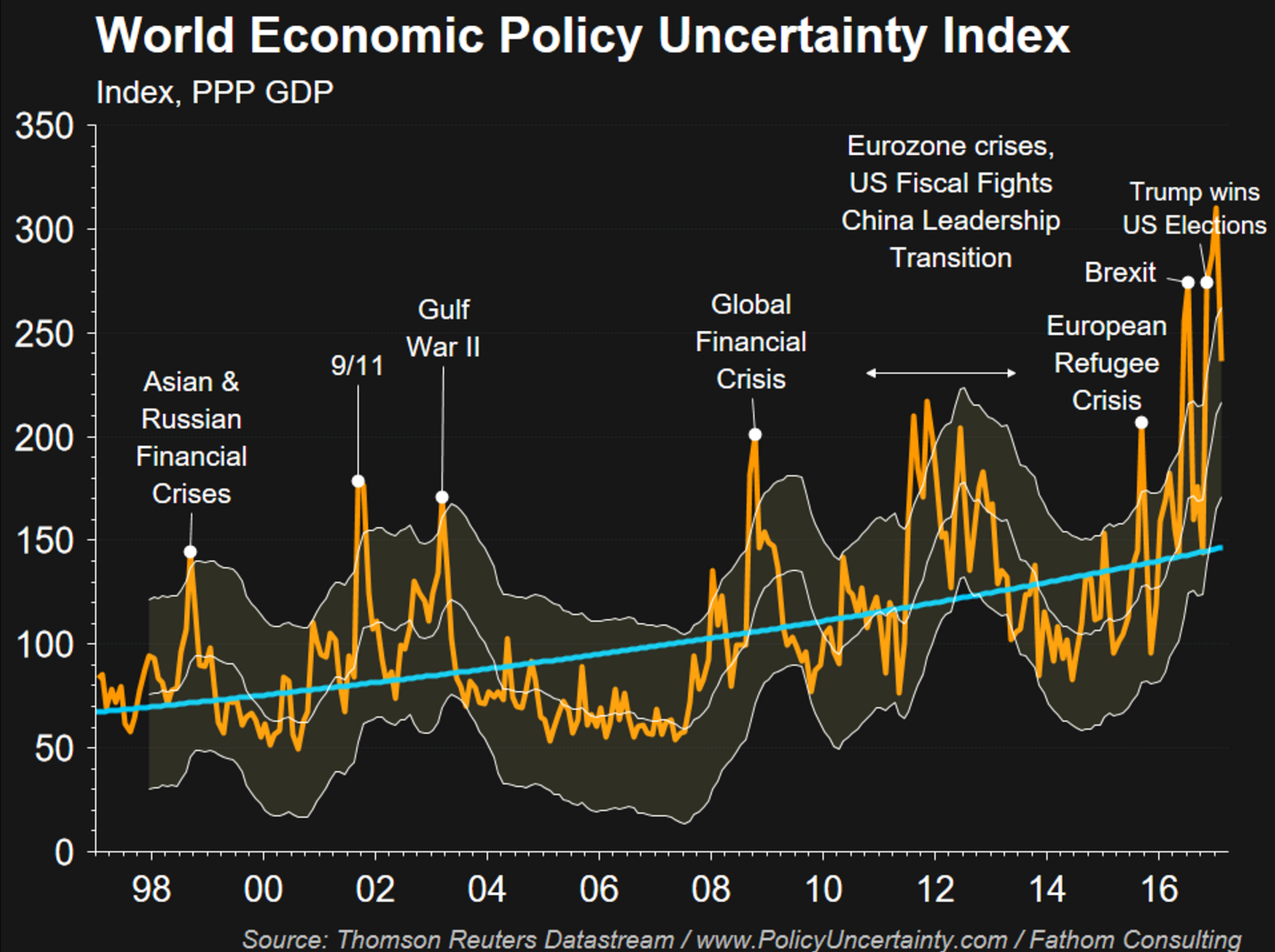

Though just like short-term debt cycles oscillate around long-term debt cycles, populist movements oscillate around secular trend lines as well. While the long-term populism trend is up (blue line on the chart below), we’re of the mind that we’re near the peak of the current short-term uncertainty cycle (yellow line). We expect political events to swing back towards more predictable outcomes for a while. Le Pen will likely lose.

This thought is bolstered by the outcome in the Dutch elections where firebrand Geert Wilders was handily defeated.

Le Pen losing would be a positive (however short-lived) for Europe because after France comes Germany with a big election in September.

It could be a boon to markets if Europe can blanket the flames of populism for the rest of the year. This is also why the ECB is so keen to play it loose. They are an offspring of the EU experiment after all.

Based on all this data, it looks like the coast is clear for Europe and we should pile in on the trend right?

Well… not exactly.

The bullish case for Europe is a classic George Soros-style false trend. The current rally is founded on untrue assumptions and will eventually reverse… hard.

None of the original reasons to be bearish on Europe have been settled. None of them.

The reality is that Europe is just behind Japan on their transition along the long-term debt cycle. They have structural problems that include inflexible and uncompetitive labor markets, dwindling demographics, a misguided currency union, and an increasingly troubling immigration problem that’s pulling at the seams of their already fragile political union.

Europe’s recent “recovery” isn’t so much a recovery as it is another dead cat bounce on its long road of decline.

But Soros-style false trends can be powerful moves. And if the French election plays out how we think it will, with Le Pen losing, the false trend will likely continue. We’re willing to surf long with the true-believers, but we’ll be quick to jump ship when things turn.

For more posts and information about Alex @MacroOps you can check out his website Macro-Ops.com.