This is a Guest Post by Alex @MacroOps which was posted originally at: Lessons From A Trading Great: Jim Leitner and is posted here with permission.

Jim Leitner is the greatest macro trader you’ve never heard of. He was once a currency expert on Wall Street, pulling billions from the markets, but now he plays the game through his own family office.

Leitner understands the Macro Ops “go anywhere” mentality better than any other trader:

Global macro is the willingness to opportunistically look at every idea that comes along, from micro situations to country-specific situations, across every asset category and every country in the world. It’s the combination of a broad top-down country analysis with a bottom-up micro analysis of companies. In many cases, after we make our country decisions, we then drill down and analyze the companies in the sectors that should do well in light of our macro view.

I never lock myself down to investing in one style or in one country because the greatest trade in the world could be happening somewhere else. My advice is to make sure that you do not become too much of an expert in one area. Even if you see an area that is inefficient today, it’s likely that it won’t be inefficient tomorrow. Expertise is overrated.

He’ll jump into any asset or market, no matter how esoteric. Some of his craziest investments include inflation-linked housing bonds in Iceland and a primary equity partnership in a Ghanaian brewer. He even had the balls to jump into Turkish equities and currency forwards with 100% interest rates and 60% inflation during the late 90’s… the man is a macro beast.

FX Trading

Leitner was one of the first traders to understand and implement FX carry trades. A carry trade involves borrowing a lower interest rate currency to buy a higher interest rate currency. The trader earns the spread between the two rates. Here’s his own words from Drobny’s Inside The House Of Money:

The most profitable trade wasn’t a trade but an approach to markets and a realization that, over time, positive carry works. Applying this concept to higher yielding currencies versus lower yielding currencies was my most profitable trade ever. I got to the point in this trade where I was running portfolios of about $6 billion and I remember central banks being shocked at the size of currency positions I was willing to buy and hold over the course of years.

FX carry trades can be extremely lucrative. But if you get caught holding a currency during a surprise devaluation, it can instantly erase all your profits and them some. Leitner was able to protect himself by keeping a close eye on central bank action:

I was always able to sidestep currency devaluations because there were always clear signals by central banks that they were pending and then I just didn’t get involved. Devaluations are such a digital process that it doesn’t make sense to stand in front of the truck and try to pick up that last nickel before getting run down. You might as well wait, let the truck go by, then get back on the street and continue picking up nickels.

Leitner understands that currencies mean revert in the short-term and trend in the long-term. He’s explored the use of both daily and weekly mean reversion strategies:

The other thing that is pretty obvious in foreign exchange is that daily volatilities are much higher than the information received. Think of it like this:

The euro bottomed out in July 2001 at around 0.83 to the dollar and by January 2004 it was trading at 1.28. That’s a 45 big figure move divided by 900 days, giving an average daily move of 5 pips, assuming straight line depreciation. Say one month option volatility averaged around 10 percent over that period, implying a daily expected range of 75 pips. That’s a signal-to-noise ratio of 1 to 15. In other words, there was 15 times as much noise as there was information in prices!

Noise is just noise, and it’s clearly mean reverting. Knowing that, we should be trading mean reverting strategies. In the short term, it’s a no brainer to be running daily and weekly mean reverting strategies. When things move up by whatever definition you use, you should sell and when they move back down, you should buy. On average, over time you’re going to make money or earn risk premium.

Options

No one has mastered global macro options better than Leitner. He knows when they’re overpriced and when they make a great bet:

Short-dated volatility is too high because of an insurance premium component in short-dated options. People buy short-dated options because they hope that there’s going to be a big move and they’ll make a lot of money. They spend a little bit to make a lot and, on average, it’s been a little bit too much. When they do make money they make a lot of money, but if they do it consistently they lose money. Meanwhile, someone who consistently sells short-dated volatility, on average, would make a little bit of money. It’s a good business to be in and not too dissimilar to running a casino. So there is a risk premia there that can be extracted. (Side note: this is the risk premia we harvest in Vol Ops, one of our portfolios in the Macro Ops Hub).

Longer-dated options are priced expensively versus future daily volatility, but cheaply versus the drift in the future spot price. We need to make a distinction between volatility and the future drift of the currency. Since the option’s seller (the investment bank) hedges its position daily, it makes money selling options. Since some buyers do not delta hedge but instead allow the spot to drift away from the strike, they make money on the underlying trend move in the currency. So both the seller of the option and the buyer make money. The profit for the seller comes from extracting the risk premia in the daily volatility, and for the buyer it comes from the fact that currency markets tend to exhibit trending behavior.

We had a study done on the foreign exchange options market going back to 1992, where one-year straddle options were bought every day across a wide variety of currency pairs. We found that even though implied volatility was always higher than realized volatility over annual periods, buying the straddles made money. It’s possible because the buyer of the one-year straddles is not delta hedging but betting on trend to take the price far enough away from the strike that it will cover the premium for the call and the put. Over time, there’s been enough trend in the market to carry price far enough away from the strike of the one-year outright straddle to more than cover the premium paid.

If the option maturity is long enough, trend can take us far enough away from the strike that it’s okay to overpay.

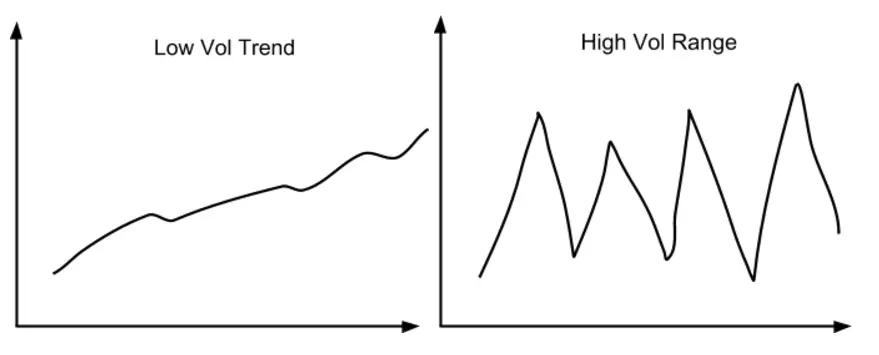

This is a key concept that very few option traders understand. High volatility doesn’t mean huge trends. And low vol doesn’t mean no trends. It’s possible to have low volatility trends and high volatility ranges.

Leitner exploits this kink in option theory by “overpaying” for optionality from a volatility perspective, but still winning from trending markets.

These overpriced long-dated options become essential in choppy markets. They allow you to “outsource” risk management. You can play for a long-term trend without the risk of getting stopped out by a head fake:

Options take away that whole aspect of having to worry about precise risk management. It’s like paying for someone else to be your risk manager. Meanwhile, I know I am long XYZ for the next six months. Even if the option goes down a lot in the beginning to the point that the option is worth nothing, I will still own it and you never know what can happen.

Psychology, Emotions, And Fallibility

Like every other star trader, Leitner has strong emotional control. He views all trades within a probabilistic framework and fully accepts his losses:

At Bankers, I came to realize that I was absolutely unemotional about numbers. Losses did not have an effect on me because I viewed them as purely probability-driven, which meant sometimes you came up with a loss. Bad days, bad weeks, bad months never impacted the way I approached markets the next day. To this day, my wife never knows if I’ve had a bad day or a good day in the markets.

Along with reigning in his emotions, he also acknowledges his own fallibility:

Another thing that I realize about myself that I don’t see in other traders is that I’m really humble about my ignorance. I truly feel that I’m ignorant despite having made enormous amounts of money.

Many traders I’ve met over the years approach the market as if they’re smarter than other people until somebody or something proves them wrong. I have found this approach eventually leads to disaster when the market proves them wrong.

It’s not possible to “crack” the market. You’re guaranteed to eventually be proven wrong no matter how smart you are. And when that time comes, you have to stop the bleeding before death occurs. The trading graveyard is littered with “smart guys” who thought they solved the market puzzle… don’t be one of them.

Investment Narratives

A compelling narrative is both a blessing and a curse.

On the one hand, understanding the dominant market narrative will keep you on the right side of a powerful trend. But it can also lure you into some dumb trades. Not all narratives are rooted in fundamental reality. Oftentimes a false trend will form and lead to a boom/bust process. Here’s Leitner’s take:

We need to quantify things and understand why things are cheap or expensive by using some hard measure of what cheap or expensive means. Then there has to be a combination of story and value. A story is still required because a story will appeal to other people and appeal is what drives markets. If there’s no story and something’s cheap, it might just stay cheap forever. But if there’s a story involved, make sure that you first look at the numbers before you get involved to be sure there is some quantitative backing to the idea.

Leitner’s team always starts with quantitative scans when hunting for equities. If the quant data doesn’t check out, there’s a higher risk of falling prey to an overhyped narrative.

In equities, we start by looking at various valuation measurements like price to book, price to earnings, and price to cash flow. It’s very important to not be too story-driven. A way to avoid that is by using quantitative screens to determine what is cheap. Once you find things that are cheap, then look for stories that argue why it shouldn’t be cheap. Maybe a stock is cheap but it’ll stay cheap forever because there’s no good story attached to the cheapness.

Longs Vs Shorts

It’s no surprise that being long financial assets has a positive expected value over time. Stocks and bonds pay a premium to incentivize investors to move out of cash and take risk.

This is why you need twice your normal conviction to go short. The system is designed to move higher over time, so you better have a damn good reason to fight that drift.

Owning assets, or being long, is easier and also more correct in the long term in that you get paid a premium for taking risk.You should only give your money to somebody if you expect to get more back. Net/net it is easier to go long because over portfolios and long periods of time, you’re assured of getting more money back. Owning risk premia pays you a return if you wait long enough, so it’s a lot easier to be right when you’re going with the flow, which means being long. To fight risk premia, you have to be doubly right.

Leverage

Mention the word “leverage” around rookie traders and they’ll run for the hills. Most think it’s a quick way to blow up a trading account. But the pros view leverage as a tool that can completely transform and enhance risk-adjusted returns. Ray Dalio is traditionally the one credited with using this concept to make billions.

Let’s say you have a 30-yr bond that returns 6% a year above the cash rate. It has a max drawdown of 20%.

You then compare it to a stock index that returns 9% a year above the cash rate. It has a max drawdown of 50%.

By applying leverage, you can transform the bond into the higher performing asset. Using 2x leverage on the long bond will give you 12% returns with 40% drawdowns. This is a much better deal than the stock index on a risk-adjusted basis. This technique is known as “risk parity.”

Leitner applies it to his fixed income investments:

When using leverage, you want the highest Sharpe ratio because you’re borrowing money against your investment, and the best Sharpe ratios are found in the two years and under the sector of fixed income. On an absolute return basis, two years and under bonds are not going to pay as much as a 10-year bond because the yields are usually lower. But the risk-to-return ratio is also very different. You could be five times levered in the two-year and get a higher payout with the same risk as a 10-year bond because of duration.

Going levered long 2-year notes is a better risk-adjusted trade than going long a 10-year note. You get the same return in the levered 2-year, but with less volatility.

Most investors can’t exploit this because they can’t use leverage. But a macro trader using futures can perform all sorts of financial wizardry and vastly outperform a typical cash-only fund.

Portfolio Construction

Over time Leitner has adapted his strategy away from traditional global macro. Instead of using market timing, trend following, and gut feel — the pillars of old school macro — he’s shifted to a multi-strategy approach.

He combines various system-based strategies across five main asset classes: Equities, Fixed Income, Currencies, Commodities, and Real Estate. His goal is to earn the risk premia present in each category. He then reserves a certain amount of his cash for special situation big bets that only come around a few times a year.

We start off by acknowledging that we are ignorant, so we need to be systematic, clip some coupons, and earn some risk premia. It doesn’t matter if it is in currencies, bonds, commodities, real estate, or equities. Of course we have to be smart about it by reading a lot, talking to smart people, and being on top of it all, while acknowledging that we’re not that much smarter than the rest of the world. Then, every once in awhile, we’re going to stumble upon an exciting idea that’s going to give us some extra alpha and the ability to outperform.

After these five main asset categories, we have a last category which we call absolute return. This is where we stick those great, out-of-the-box ideas we come across about twice a year. Sometimes we’re lucky and find major mispricings once or twice a year, and sometimes we’re unlucky and it takes 18 months before the next one comes along. When we find these fantastic ideas, we’re willing to bet up to 10 percent of our fund on one idea. One that we think will double or triple, earning an extra 10 or 20 percent return for the entire portfolio.

The absolute return category is there in order to leave us open to making unsystematic money.

The multi-strategy approach is the most robust way to allocate capital. Most of the macro legends of the 70s, 80s, and 90s have moved to a family office format and implemented something similar to what Leitner describes. At Macro Ops we too use a combination of discretionary and systematic strategies to make sure the cash register keeps ringing year after year.

For more posts and information about Alex you can follow him on twitter @MacroOps and you can check out his website Macro-Ops.com.